Film opinion: Wes Anderson films aren’t style over substance — the style is the substance

By now, even those who have never seen a Wes Anderson movie, know what one looks like.

Symmetrical framing, pastel colour palettes, characters who talk like emotionally repressed poets, quirky fonts, and of course, Bill Murray.

It’s all so distinct that the “Wes Anderson style” has practically become its own genre, with many social media trends emerging in its wake.

And with this visibility has come an old but persistent critique: that Anderson’s films are all surface, no soul.

That they’re style over substance.

But Film News Blitz’s Heidi Hardman-Welsh begs to differ.

A lack of substance?

To dismiss the art of a Wes Anderson film as being surface-level is an insult that gets thrown at visually distinct filmmakers more often than it should.

But in Anderson’s case, it misses the point entirely.

The meticulous design, deadpan delivery, and diorama-like sets form the very language he uses to explore grief, alienation, nostalgia, and the absurdity of being alive.

Anderson’s films don’t lack substance; they simply refuse to present it in the usual packaging.

READ MORE: Box office news: ‘Jurassic World Rebirth’ packs potent global bite in opening weekend

The whimsical as camouflage for existential dread

Wes Anderson’s films are often described as whimsical, and sure, they are.

There are stop-motion foxes wearing corduroy suits (Fantastic Mr. Fox), a boy scout falling in love with a bookish girl and running away on an island (Moonrise Kingdom), and an entire fictional Eastern European country dreamt up from scratch (The Grand Budapest Hotel).

But underneath the whimsy lies an undercurrent of melancholy and longing.

His characters are often emotionally stranded, clinging to rituals and routines as a way to make sense of a chaotic world.

The obsession with order, visual perfection, and with things being ‘just so’ reflects the internal states of his characters — many of whom are trying (and failing) to control the uncontrollable.

It’s a fantasy, yes—but one that reveals how humans cope with uncertainty.

‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’ (2014)

Take The Grand Budapest Hotel, arguably Anderson’s most stylised film to date.

It’s a layered narrative within a narrative, told through shifting aspect ratios, pink hotels, purple uniforms, and a perfectly ornate script.

And yet—beneath all that—is a story about the collapse of a civilised world.

It’s about memory, trauma, and how fascism creeps in while people are distracted; it is essentially a war movie in disguise, coated in a fantastical tone.

Gustave H., played with elegant desperation by Ralph Fiennes, is a perfect example of a Wes Anderson character.

He is the concierge of the elegant Grand Budapest Hotel in the European country of Zubrowska and must prove his innocence when he is framed for a murder.

He is a man out of time, clinging to decorum, etiquette, and civility in a world sliding into brutality.

The film’s opulence and beauty becomes a metaphor for the very thing Gustave is trying to preserve.

This is where style is no longer ornamental—it’s fundamental.

‘Fantastic Mr. Fox’ (2009)

One of Anderson’s most beloved and well-known films is his stop-motion adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox.

The film follows Mr Fox, a charming but reckless ex-thief who can’t resist one last big heist, dragging his family and woodland neighbours into a full-blown war with three monstrous farmers: Boggis, Bunce, and Bean.

What starts as a classic animal-versus-human tale quickly spirals into an existential crisis wrapped in fox fur, with themes of identity, freedom, otherness, and the balance between natural instincts and responsibility.

Anderson’s directing style is all over the film: the fast-paced dialogue, the symmetrical compositions, the autumn and earthy colour palette, the attention to detail in every frame.

Even the fights and action scenes unfold with an odd sense of order, all choreographed with the rhythm of a stage play.

The animation is charming, filled with handmade textures and miniature sets that offer cosy visuals, drawing viewers into this whimsical, yet serious world.

Symmetry in the age of chaos

In an era where many films chase gritty realism or hyper-edited chaos, Anderson’s formalism feels almost radical.

He doesn’t apologise for being theatrical or artificial; instead, he leans into it.

And there’s something oddly comforting about the ordered worlds he creates, especially when real life feels anything other than ordered.

The world could be falling apart, but at least in Anderson’s universe, the trains run on time, even if they’re full of emotionally stunted characters carrying vintage suitcases packed with unspoken trauma.

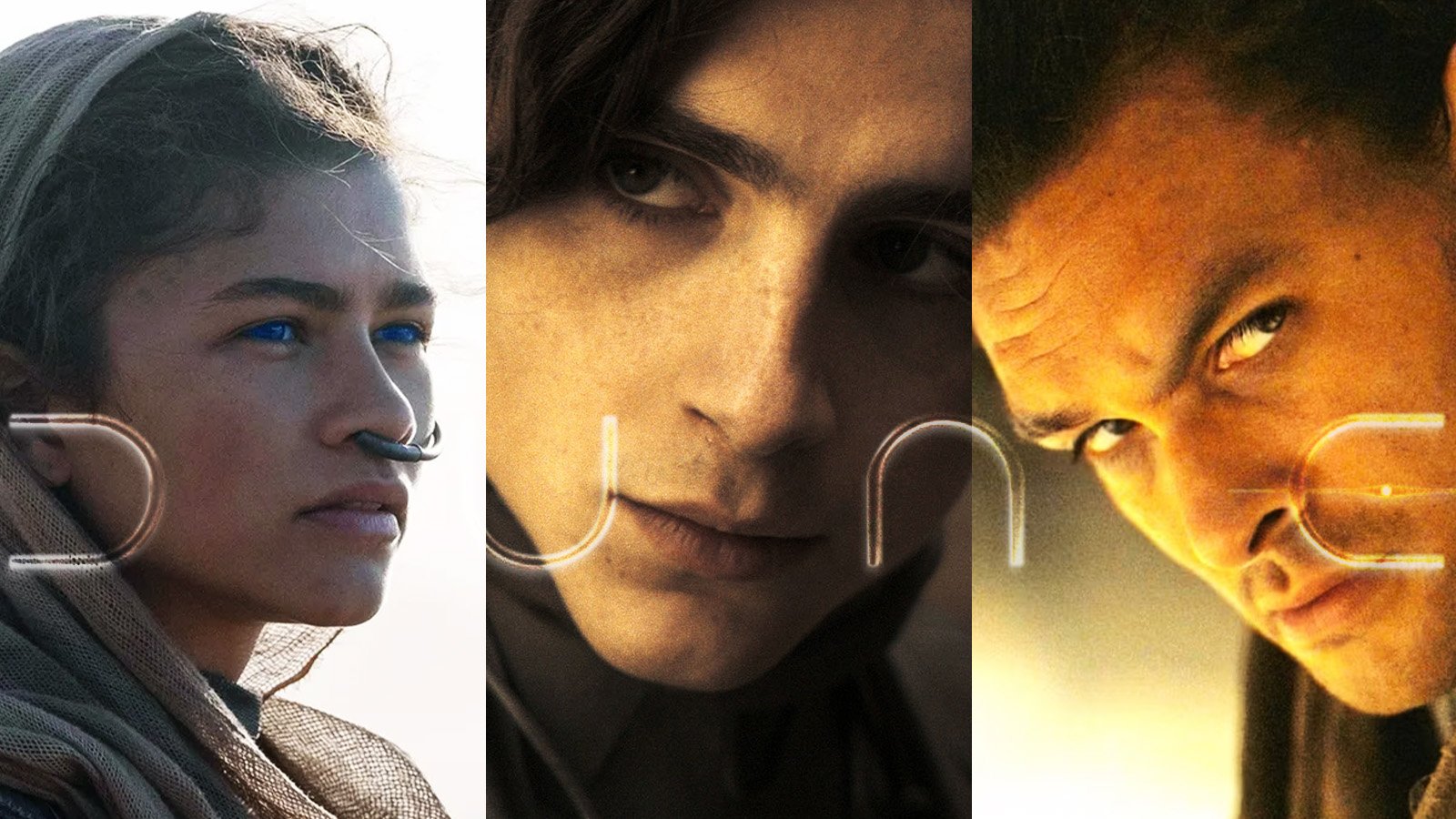

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE: Film news: ‘Dune: Part Three’ loads up on stars for trilogy

Final frame

The critique that Wes Anderson films are “style over substance” only makes sense if you believe style and substance are separate things, which, in great filmmaking, they never are.

In Anderson’s case, style is the lens through which we feel everything.

His films trust the audience to feel something, not because they’re told to, but because they’ve been invited into a world where every frame is a feeling.

If anything, Anderson’s commitment to formal beauty is a rebellion against lazy storytelling.

To dismiss it, is to miss the point entirely.

You don’t need shouting matches or handheld cameras to make something emotionally resonant.

Sometimes all you need is a perfectly framed shot of a sad man in a velvet blazer, staring out a train window while a classic French pop song plays.

And that, my friends — is cinema.

READ NEXT: Film opinion: How ‘Wicked’ took the film industry by storm